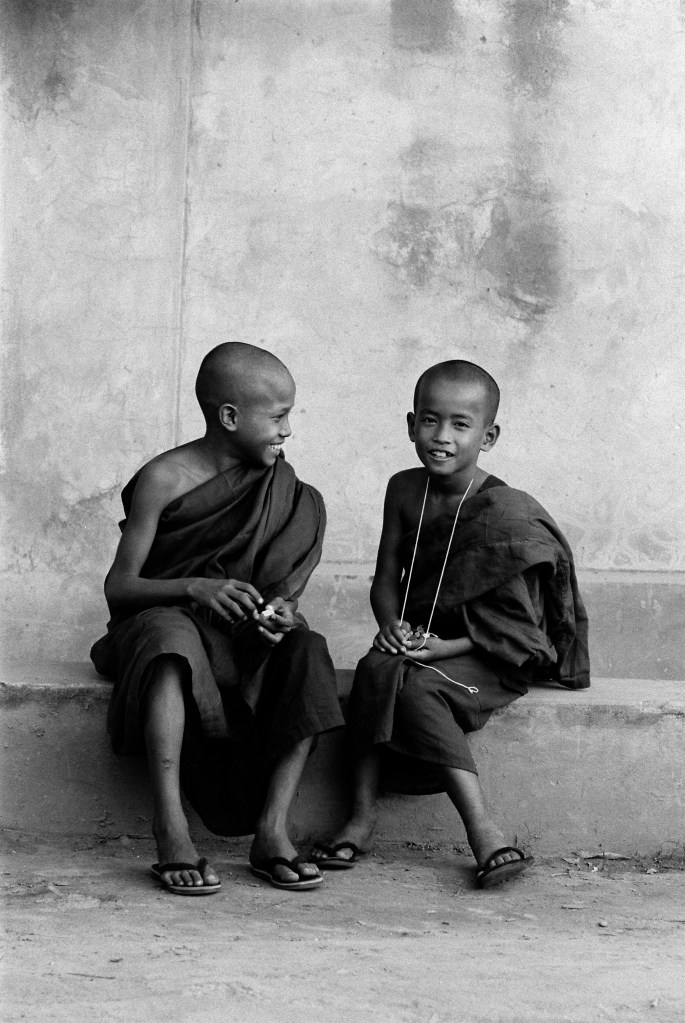

Pyinmana, Myanmar 2018

As Spielberg’s most famous character is currently being revisited without him, I feel it is time for an opinionated retrospective. The mainstream press holds on Spielberg’s every cinematic word (looking at you, Empire). Everyone sings his praises. Who wouldn’t want to sit and chat movies with Spielberg? Who wouldn’t want to be this guy?

I feel it’s time a sensible voice added something new to the discussion.

Ah Spielberg, we all know the legend: the shy Jewish kid that went from a product of divorce to the youngest TV director on the lot to the most successful and influential filmmaker of all time. While most mortals can only dream of wealth, fame and success like his, he spent $200 million on a yacht and then had to be talked into going on a cruise in it by his staff.

It’s been nearly 32 years since Indy rode off into the sunset, 30 since Jurassic Park and Schindler’s List. As his remake of Westside Story looms, many might ask has he lost his touch? Of course, he is perfectly entitled to have done so. It is the medium-defining masterpieces of his early career that guarantee his place in the film library on Mount Olympus. Few are lucky enough to have even a lick of that much ‘touch’ or being afforded the opportunity to demonstrate it.

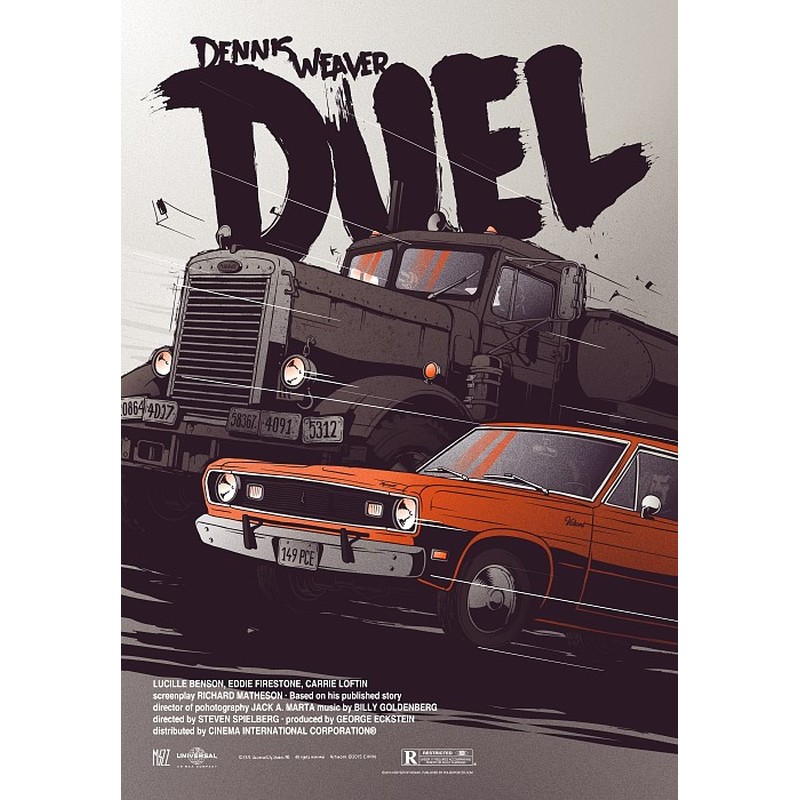

What glorious exercises in cinema those early works are: Duel is a solid exercise in tension. Jaws is so good it hurts. Those barrels bobbing around in the water get me every time. The sublime edit of Raiders of the Lost Ark, with its flawed hero bungling his way through his adventures to the Divine saving the world, is the definition of timeless.

Temple of Doom is highly uneven, the character is more a superhero and loses his charming flaws, yet the filmmaking is awe-inspiring. Witness the colour design, the editing. There are obvious defects in that eras effects but we can forgive that. For anyone who wants confirmation of who really shot Poltergeist, look no further than the tracking shots/close ups used in Doom and how they are replicated exactly in the horror film.

The Last Crusade (if only) is sublime, the only error being the casting of Alison Doody; just cast a German actress! There can’t be a shortage of them. X never marks the spot. With any luck Marcus has the Grail already! Donated by some of the oldest families in Germany! I see you, Tom Stoppard.

Then there were the nineties. Deux Ex Machina entered the room.

I’m going to make a bald claim here – Jurassic Park is not a good film. It is a poor adaption, over-simplifying a great novel and shoe-horning in unnecessary drama with annoying child actors which was soon to be a defining trait (okay, cliché) of his work. Cliché no. 2 is the Deux Ex Machina ending: they’re doomed… they’re doomed… oh they’re not. Truly a terrible way to write yourself out of a corner.

He pulled the same trick at the end of Saving Private Ryan, yet another massively overrated entry. Witness critics forever shouting about the brilliance of the beach landing sequence, staged straight out of the nightmares of John Ford and Robert Capa. But then what? A cast of faceless no-marks and Tom Hanks. Didn’t that start a worrying trend! For the record, Shakespeare in Love deserved the Oscar. War of the Worlds was ruined by more unnecessary child clichés – the teenage girl with the maturity of an adult, prone to panic attacks whenever the script needed it. The son surviving undercuts the drama in the situation; there are no stakes, Steven!

Then, of course, there is the mighty Schindler’s List. Three hours of near flawless filmmaking ruined in the last five minutes by saccharine schmaltz. “I could have done more” …. Blub blub. Seriously? That’s not how real people act. Schindler watches the workers celebrate the end of the war. Gift of the ring. He walks to his car, gets in. Looks around. Shadow in the car. White headlights, dark screen. Drives off. No words. Fade out. It doesn’t need signposting so explicitly. Visual poetry ruined by the very emotionalism the film had avoided so well until that point.

Or is it just a well-shot exploitation movie? Jew porn, as the famous playwright noted at the time. Come see the horrors these poor people suffered! It’s shocking! ‘Entertainment’ is one of the first words on the screen. You decide. Terry Gilliam pointed out the film still has a happy Hollywood ending. The Holocaust didn’t for 6 million people.

As for AI, well, that’s a god-awful piece of crap – two thirds a watchable story if we consider it a warning of how creating an immortal robot child would be an act of cruelty. Cut the ending at spending eternity in a glacier and you have a powerful statement. But robot/aliens? And ‘mommy’? Vomit. The publicity at the time made the point Kubrick took years to shoot, whereas Spielberg took mere weeks. Doesn’t it show. You almost have to feel sorry for the marketing people that had to hawk this rubbish.

Minority Report is without doubt the best of his later films. The cinematography is beautiful and the story of an abducted child handled with far more restraint than could be expected. It’s a shame the writers changed the original short story’s ending. The casting of Max von Sydow makes the antagonist obvious from the first scenes.

And then? Some tedium with a horse, some Daniel Day Lewis and some unremarkable historical pieces. He phoned in Crystal Skull, added CGI monkeys. Ready Player One, whilst technically flawless, is a hollow story of the little people versus the corporation. No hypocrisy here, Mr Spielberg.

All artists peak, all decline with age, riches and success. But then he made his Tintin movie with visual invention that showed much of the old flare. More of this please.

Let us not forget his involvement in many other cultural crimes: Brett Ratner, JJ Abrams, the John Goodman Flintstones movies and Seaquest DSV to name but a few. Nuking the fridge became Hollywood shorthand for terrible story-telling.

Recently we have had Indy 5’s James Mangold’s Twitter meltdown and The Force is Female. Smart money is on Indy dying on the moon and being lectured for being part of the patriarchy. Spielberg clearly saw what Disney did to Star Wars and stayed clear. You have to respect the man for that and wonder why Mr Ford’s agent would allow him to be part of the trashing of his own legend for a second time.

We have no right to ask the man for anything. He enriched the 70s, defined the 80s and rocked the cinematic world in the 90s. But who wouldn’t want one more fantasy film? One more return to the purity of Raiders of the Lost Ark and Poltergeist?

Can you do it, Mr Spielberg? I’m not ashamed to beg. We’d willing forgive the Deux Ex Machina, the awful child drama, the CGI monkeys and War Horse for just one more piece of cinema to that old standard.

I constantly get told that its prohibitively hard to get a job in cinema – that the young should chose careers that are ‘useful’ for society, meaning business studies and computing. Yet, to those that dismiss the creative impulse and the dreamers, I ask What did you do during lockdown? Now tell me the world doesn’t need imaginers and creators of fantasies.

Come on, Mr Spielberg. Show us how it’s done. The autobiographical movie won’t cut it.