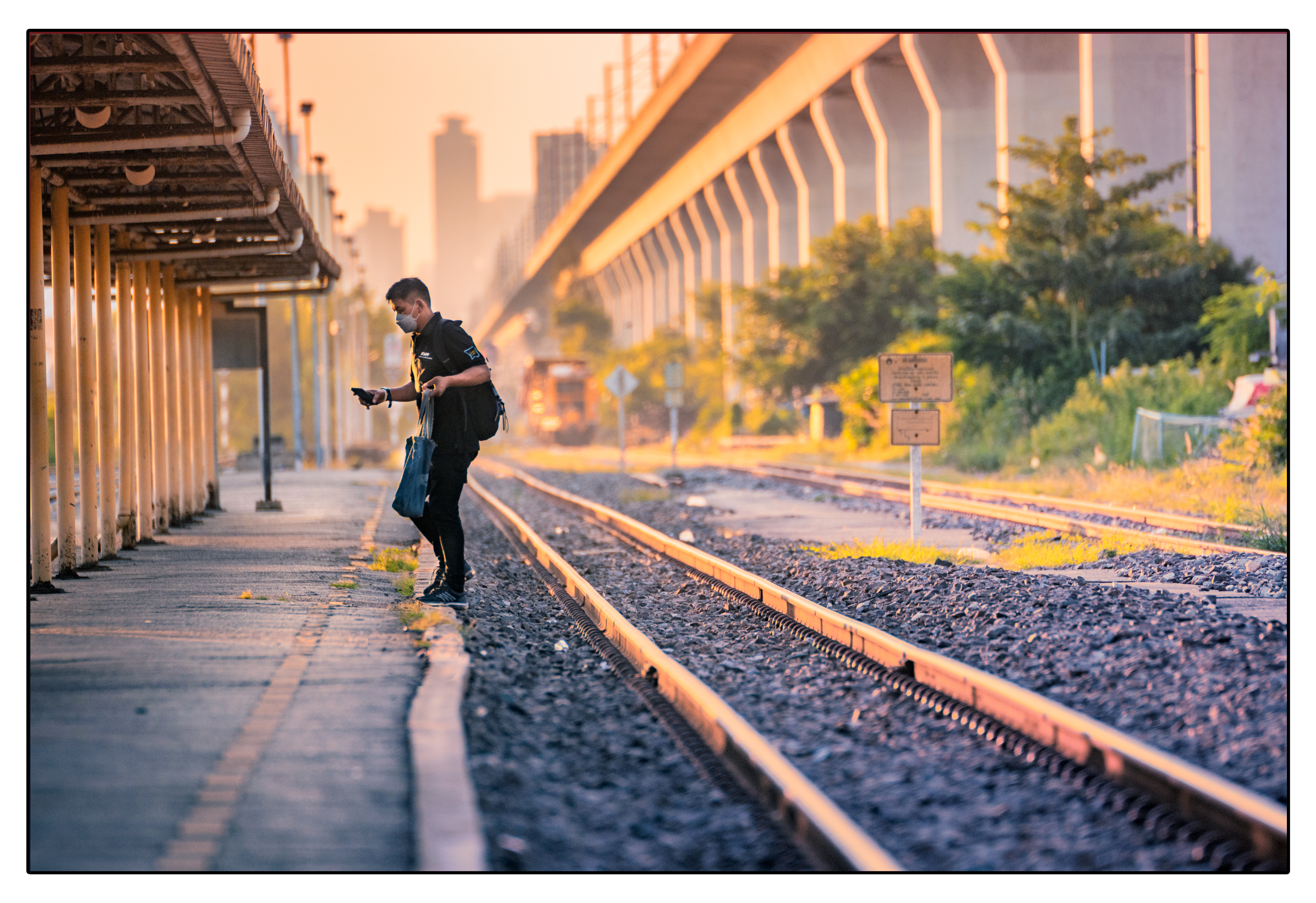

Ramkhamhaeng, Bangkok, 2025

Showrunner Steven S. DeKnight returns to the Roman era with Spartacus: House of Ashur. The show is an alternative history set in the same world, with a minor villainous character from the original show resurrected and rewarded with a gladiator school by his patron. Can the new show live up to the extremes of nudity and violence that have made the original such a winner on streaming? Or has yet another great show had its USP sanitised away?

Starz

1 episode of 10 seen

Starz’s Spartacus series retold the story of the gladiator who led an army of freed slaves against Rome. The very idea was sacrilegious to many, given the reverence for the Stanley Kubrick/Kirk Douglas 1960 original.

The series was executed in the style of Zack Snyder’s 300 and painted a bloody picture of a will-to-power world where might was right and there was no justice for the impoverished majority. It won itself almost immediate goodwill with its sheer commitment to being as extreme as a show could be, just shy of being a snuff movie filled with hardcore porn. Can such a show possibly return unaltered in a vastly more conservative 2025?

It was the kind of show you felt sick after watching, as it didn’t flinch from showing the effects of gutting a man with a sharpened piece of rusty steel. The image of fresh corpses dragged from the arena with a meat hook is not one the viewer will forget.

However, it wasn’t merely a mindless video nasty. It was also a brilliantly written world of intrigue, scheming and violent one-upmanship. Never had the Roman Empire been depicted in such seductive and dystopian terms. Everyone spoke with deliberately stylised speech; the combination of word and image left the viewer with the sense the showrunners committed to a unique vision in a notoriously noncommittal industry. The show had signature authorial style.

The makers won more goodwill when it was revealed the original star – Andy Whitfield – had stage four cancer, and they shot a prequel series delaying the need for him to be on set. Sadly, he died, aged 38.

The two series that remained – once recast – went on to push the anti-slavery message. It was also riotously entertaining and brilliantly plotted. Yet, it also built sympathy for the characters, especially those who started out as little more than violent beasts and died as dignified free men. Of course, the show’s ending was inevitable: the slave army crucified along the Appian Way. The skill was how it got the characters and the audience there. The final battle memorably showed how to defeat an unbeatable gladiator in single combat and still managed to show his crucifixion as his imagined public triumph. Such flourishes show how the series rose above Kubrick’s celebrated ending.

Was the show just gore-heavy softcore pornography? No – it was a highly intelligent and empathetic story disguised as trash, deliberately combining sensationalism with excellent storytelling to invoke the world and the stakes. It succeeded to such a unique degree that DeKnight kicked the sands of literal exploitation cinema in the face of the previously unassailable Stanley Kubrick. The show was raw. It wasn’t an open wound – it was a severed artery. Unlike his characters, he took on the might of Rome and won. The question in 2025 is whether he can do it again.

In the first episode (of ten) of Spartacus: House of Ashur, the newly minted title character has saved Crassus – the richest and most powerful man in the empire – from Spartacus and his army, and is given the gladiator school where the story started as his reward.

In a fit of pique, and after a speech mocking those glorifying the gladiators in previous shows, Ashur beats his best prospect to death with a broken wine jug. Hubris, of course, as this proves his undoing later, when he manages to gain his ludus admittance to the gladiatorial games but can only field a second-rate man. That gladiator speaks of Spartacus-like murder and rebellion and dies violently, mocked by the powers of the town and pitied against three – intentionally hilarious – dwarves. Ashur decides he needs to stage a shocking affront to public decency to gain the attention he deserves. He takes possession of a Nubian slave after witnessing her throwing Roman soldiers around like rag dolls and plans to pit her against men in the arena.

Ashur states such controversy will attract a new audience. For Starz’s sake, it is hoped he is correct. Dwarves played for comedy and a superhumanly strong woman feel suspiciously like a studio mandate to broaden the show’s demographic appeal. And that’s a proven way to alienate your core audience.

Where will the season take the story? The gods were not known for resurrecting men out of pity. Is this to be the story of Ashur’s ignoble fall or the glory of his rise? Either is fine, but regardless of the narrative direction, Starz’s ‘We’re all adults here’ banner is hopefully a mission statement – giving an inch on tone and content will tank its prospects faster than facing those dwarves in the arena.

3/5 Were we not entertained? The first episode of Spartacus: House of Ashur can’t be faulted on technical execution but wobbles on brand fidelity. Accepting time will have changed the tone, and absent the revenge/rebellion plot, the series premiere sets a cautiously familiar direction. Starz… don’t screw this up.

Dr Andrew King’s coming book describes today’s Tinder-dominated dating scene as an unholy blend of anxiety projection, the distorted politics of self-esteem, and impersonal algorithms. As a result, modern dating is wholly inadequate for solving the age-old problem of mate-selection.

It’s not every day that I ask a man about dating advice, especially not one who resides in central Bangkok. Fortunately, I’m speaking to a PhD-holding former journalist and not a fugitive sex offender in a Singha beer vest and elephant trousers. Of course, it helps his credibility that at no point during our interview does he ask me for money or talk knowledgeably about STDs – so you know you’re safely above the average expat.

As he talks – eloquently – I start to suspect this isn’t sneering pickup artistry as I feared, but a timely addition to the literature on our current cultural problems. If you’ve found Jonathan Haidt’s books required reading, you should add Dr King’s to your list. In a world paralysed by cultural relativism, a historical study feels almost radical.

Cultural Representation

He says: “My PhD was about indigenous people being seen as sexy in the media. If you’re seen as sexy, you become marriageable. You’re not another race to be avoided – you’re people you can have a relationship with.

“After I finished my PhD, all the funding used government money to solve worthy social problems – having more women play football or better dating apps for gay guys. There were committees and groups who had guidelines for non-traditional research outcomes – this whole area of not-publications, not-peer-reviewed articles or books. It was: ‘What value does that add to the community?’ Academia was how can we solve problems that don’t really exist.”

Asking himself whether he wanted to get good at extracting money from the Australian Government, he realised: “Academia was full of bullshit. A PhD was useless. So, I thought: ‘Okay, I need some real skills.’”

He spent many years working as a journalist in Myanmar, speaking with people free of what he describes as the imagined social problems occupying so many of his scholarly peers. He found writing about the pragmatic concerns of subsistence farmers and pagoda-enthusiasts more rewarding.

Background

Andrew King was born in Northampton General Hospital in 1976, and to put as much distance between them and the shoe trade as possible, his family moved to Perth, Australia in 1990. Tall, handsome, you’d easily imagine him riding a surfboard if you grew up watching Neighbours. He has a taste for flowery collared shirts. No trace of an English accent remains.

He doesn’t strike you as the sort who’d need self-help guides to win a mate. Yet, after a break-up, he says he read Models: How to Attract Women Through Honesty by Mark Manson. His current journey started there.

“I was sharing a house with a guy with Asperger’s,” he says. “He was very good at picking up women but not great with relationships. Simon Baren-Cohen looks at how men and women’s brains differ, talking about men having systematising brains, while women are better at identifying emotions and facial expressions. That made sense when I considered my ex-girlfriend – who was extremely keyed into others’ emotions. My Asperger’s flatmate was terrible with emotional cues, but great at remembering the exact place you put the milk in the fridge two months ago.

“I wanted to know more about those differences in people between these two extremes, what that means for attraction and relationships, and how much the culture and the education system had completely lied to me about it.”

Researching the Dating Scene

This led to a serious read of dating advice going back centuries.

“In the 1800s dating was ritualistic,” he says. “Etiquette was the main thing and that was more about chivalrous public displays – costly signals that took a lot of time to develop. Learning French, Latin, traveling, having knowledge of foreign culture was something that a man could display as cultural capital to attract a woman. Women were encouraged to show themselves as being a worthy mate by taking care of the home.”

He says urban life introduced a recognisable consumer’s dilemma into this Jane Austen Mr-Darcy-needs-a-wife picture. “Suddenly people have more choice, and relationships become more chaotic. People don’t know who to like because they used to meet through work, in their community, or just have an arranged marriage.

“Chivalry started to break down around 1900. The ideal at the time is to take care of your husband and wife, and to overlook some of their foibles. He says the absence of men post–World War Two changed things and a more clinical scientific approach took over the advice manuals.

“There were so few men there, they basically had a match.com approach – fill out a survey. Who are you going to be most compatible with? Personality type wasn’t developed as much then, so it was more ‘What’s your profession?’ ‘What’s their class status?’”

The 1970s saw an explosion of swinging clubs, singles bars, and more opportunity for consequence-free sex. He says: “There was still a lot of shaming, but it was cultural capital that you could claim. If you’re a university-educated woman you could say ‘I want to go to these clubs. I want to hang out and have sex.’ You could have sex and then just move to the next guy, but you still had to have attachment to this person. The guy would be bored with these girls and move on. It created a lot of anxiety and stress for women.”

Pickup artistry developed in the 1980s. For males, advice was very mechanical and very science based. For women, it was all about feeling good, masking anxiety behind rigid rule-based advice – wait 48 hours before you can call him up, don’t answer straight away. He says trusted sources of advice were all about manipulation and displaced anxiety. The 1980s turned the dating scene into yet another commodity market. Lots of us went home with buyer’s remorse.

Today’s Grim Picture

He says dating today is broken. His is a dystopian vision of everyone getting high on a defence mechanism cut with unearned self-esteem and sublimated guilt. He points out current thinking fixates on solutions to social problems aligned with today’s divisive academic fads rather than obvious practical ones – such as keeping the species reproducing. You’d think failing to solve the declining birthrate would have alerted keener minds to academia’s cloud-cuckoo-land pretensions sooner.

“All the contextual cues that people in previous generations used to assess mate value have been stripped away and left to algorithms. Pickup artistry – which the mainstream is very hostile towards – contains some good advice, such as going cold turkey on social media and pornography. Such a return to Victorian-era abstinence reimposes scarcity that forces us to seek social validation and sex in the real world, with real people, not on the phone or internet.”

Ah, yes. Phones and the internet. Enter the current lost generation. What are we to do with Gen Z?

“Their fear of risk, wanting safe spaces and trigger warnings, seems to come from the therapeutic culture of their boomer grandparents who embraced the idea that everyone was special, rather than fostering connection, negotiation and meaningful conversation.

“Parents of each generation seem to outsource their parenting to education, nurseries, TV and now screens that often leave families – using Sherry Turkle’s phrase – alone together. Hence the anxiety about meeting people outside of your social group or circle.”

The implication is we need to get the kids in a room, talking and learning how to navigate a trauma-filled world if we are to produce a Gen Alpha and Beta psychologically – and evolutionarily – suited to a reality that isn’t getting any friendlier. Is there any hope for those lusty lonely hearts cruising the bars in Bangkok?

“They’re their own breed of weirdness,” he says with a groan. “They deserve their own book.”

Dr Andrew King’s book Costly Signals: How Evolution Shaped Centuries of Dating Advice will be published in 2026.

Top Gear and The Grand Tour producer Andy Wilman gives his perspective on two decades of auto-motive chaos, endless quiche buffets, and a graphic warning about dodgy salad. His memoir is a deceptively simple nostalgic look at a cultural juggernaut that presented as chaos but was actually precision engineering, arriving regularly like a rusty Volvo pulling a caravan.

By Lee Russell Wilkes

Mr Wilman’s Motoring Adventure: Top Gear, Grand Tour and Twenty Years of Magic and Mayhem by Andy Wilman, published by Michael Joseph.

Andy Wilman – the producer of both the BBC’s Top Gear and Amazon’s The Grand Tour presents a licenced and on-brand memoir full of ‘I miss those days’ sentimentality, swearing and stories about sharing petrol station snacks with cast and crew. It’s easy to imagine the manuscript spent a lot of time with lawyers prior to release as the book contains nothing sensational. There’s no ‘The Andy Wilman Story’ TV movie coming out of this one.

Top Gear and its sequel The Grand Tour were a tabloid fever dream of populism and shameless entertainment. The presenters Clarkson, May and Hammond were worldwide celebrities. Despite its obvious cultural impact – or probably because of it and the shameful manner their TG ended – no-one involved has yet received any public honour. Wilman laughs how their irreverence meant they’d never gotten a BAFTA. Their two-fingers in the air show was welcome Sunday counterprogramming to all those turgid glorifying-the-landed-gentry costume dramas the BBC so shamelessly cranks out. The revamped Top Gear was proof the public wanted tabloid sensationalism. Fortunately, at their peak they had 350 million viewers worldwide and that brought revenue. Lots of it. The BBC liked that more.

Andy Wilman and Jeremy Clarkson attended Repton School, in Derbyshire together. After graduation, Clarkson joined a local paper, while Wilman deliberately failed the Sainsbury’s management exam. Jeremy talked him into giving journalism a try and Wilman was later feature editor at Top Gear Magazine. By accident of course, rather than skill and hard work. Clarkson and he worked on the original Top Gear show when it was a safe – if dull – regional programme based in Pebble Mill, Birmingham. Clarkson recruited his old friend when he pitched his new vision for the show.

The best of his how-it-all-began stories tells how Hammond got his presenter’s job. After a truly awful camera test, Richard went into a long self-pitying rant about always pulling defeat from the jaws of victory. He explained how the highlight of his radio career had been his on air reading of a list of farm animals for sale. By the time he’d finished, cast and crew were laughing uproariously. Thus, did fate turn.

Running his finger up and down Cameron Diaz’s nose as the cast and crew looked on in envy seemed Wilman’s high point. The low point was being asked to stop quietly singing a Who song by the man next to him. That man was the band’s lead singer Roger Daltrey – he even pointed out Wilman had gotten the lyrics wrong.

After Clarkson was let go by the BBC, they all signed on for version 2.0 – The Grand Tour – on Amazon Prime. Their opening film of Clarkson leaving a wet dreary London to drive a muscle car in the desert outside of Los Angeles is a masterpiece of audience manipulation – dull colours, slow sad music that builds to a brilliantly edited colourful climax. It cost 2 million pounds. Wiman says he even got a good luck email from Jeff Bezos.

Wilman describes awkward pitch meetings with bemused studio executives. Yet, once they saw the speed with which the crews moved and the quality they produced, all went smoothly. Clearly these boys knew a thing or two about making a first-class show. They produced 32 shows with relative ease. The streamer wanted 22 more but settled for what became the travel specials.

Their collective mastery of the genre they created grows more obvious when he notes they had no trouble luring old Top Gear colleagues to join them at Amazon. Loyalty, perhaps. But presumably freelancers go where the money is. During their life-threatening dash through the night avoiding violent mobs in Argentina, one of the crew was filming on his phone. Casual? No. Solid professional instinct? Yes. Reducing grown men to tears – as these films did – is not casual happenstance. Ask everyone that’s tried to copy them.

Wilman’s book underplays the team’s obvious media savvy intelligence and mastery of the medium. Who cares if the whole edifice of wacky laddish spontaneity was scripted and contrived. They sold it well enough. One can love the magician while knowing it’s all smoke and mirrors. You get the impression that’s what Wilman’s book is – a book-length retrospective playing to their brand.

His book isn’t one more chance to revisit old friends because they were never your old friends to begin with, that illusion was the show’s tabloid register. No. It’s saying goodbye to some slick, manipulative and brilliantly conceived entertainment rooted in the monoculture public service ethos of 20th Century broadcasting. What else should we have expected from a couple of old boys who worked at the heart of the BBC?

Steve Gainer’s Everything Cinematography

YouTube, 5 episodes

Social media suffers no shortage of lifeless movie channels. Yet, Steve Gainer’s Everything Cinematography is a welcome break from anonymous YouTubers endlessly reshuffling the same old talking points. The canon has long since settled. Refreshingly, Gainer focuses not on the movies but on the cameras and the operators responsible for these classics. For some – including Gainer – the archaic technology housed in the American Society of Cinematographers’ museum is treasure that rivals any mediaeval reliquary.

Why would anyone care about antiquated cine-film cameras? Celluloid is a long-dead shooting medium, and the derivative slop filling cinemas today means the art form is becoming less relevant with each passing year. Of course, this isn’t just a curated eBay page of dusty old cameras from granddad’s shoe cupboard. These are the tools that shaped our cultural heritage and our visual grammar – forceps that birthed the movies. We’re talking the actual hand-cranked camera Billy Bitzer shot Griffith’s Birth of a Nation with, and the camera Greg Toland and Orson Welles dug into the floor for Citizen Kane.

However familiar with these films we may be, looking at the tools used to make such works offers a refreshing new angle. Gainer tells us about the practical issues the pioneers faced and asks who the crazy fools were who risked life and limb to make movies.

For instance, cinematographer Bernard Mather was killed by a blow to the head from a frozen block blasted away from the pack ice surrounding the ship on Amundsen’s Arctic voyage. It’s obvious that Gainer holds such people in the same high regard that others reserve for Picasso or Turner.

It’s hard to imagine a world without Citizen Kane, yet despite the reverence for it, few consider the tools – and by extension the legions of people who made them. Gainer’s channel is a celebration of the pioneering spirit, both technical and human. Someone innovated these cameras, and real needs were met. For an industry that celebrates artistic creativity, it’s nice to see a skilled cinematographer focusing on the practical issues – and the equally important technological innovation that made the movies possible in the first place. Whatever Welles’ talents were, he still needed a director of photography, a crew and cutting-edge equipment.

Gainer makes clear that analogue technology has its own lustre. Seeing century-old technology functioning has its own necromantic fascination. That Gainer jumps up and down with glee as it does so, makes these machines more human. If it’s hard to imagine yourself enjoying the talk of pull-down mechanisms and slide-over parallax viewfinders, trust that Gainer sells it.

With all the forgotten mechanical marvels on show, it’s clear no-one’s going to get excited about today’s solid-state digital cameras a century from now. Nobody reveres last year’s iPhone. Circuit boards don’t have animus.

Anyone who has ever looked through a still or movie camera, or lost hours in Lightroom, Photoshop, or Premiere Pro will recognise something of themselves here. It’s perhaps hard for many to imagine how someone might be singularly focussed on making images to the exclusion of everything else. We photographers know it’s an obsessive’s pursuit, and Gainer helps us recognise something of ourselves in those pioneering fellow travellers from a century ago – these marvels didn’t just show us the stars and dreams of yesteryear, they help us realise there but for the grace of God went we.

The introduction to the ASC’s camera collection starts here and continues on Steve Gainer’s Everything Cinematography. Interview here.

Three seasons, Apple TV+

The third season of Apple’s Isaac Asimov adaptation Foundation settles into cutting-edge filmmaking and beautiful colour design, quickly becoming compelling – if flawed – viewing.

Foundation’s premise remains recognisable from Asimov’s books. In the far future, Hari Seldon, a mathematician, hits upon a method of accurately predicting the long-term future and foresees the galaxy-spanning empire’s fall and thousands of years of barbarism. He is exiled for suggesting a method of limiting that dark age to a thousand years. He sets up the Foundation to navigate the chaos and save humankind. Of course, it’s never that simple.

At the start of this third season, the Foundation has survived two of Seldon’s predicted crises to become a legitimate political force. The military defeats at the end of season two mean the empire’s dynastic hold on galactic power has been waning for centuries. Each of the three cloned emperors harbour doubts about their nature, purpose and legacy. A new figure – The Mule, a psychic with a talent for conquering worlds – appears, challenging the existing order and the accuracy of Seldon’s maths.

The older actors – Jared Harris and Terrence Mann – steal every scene they are in. Lou Llobell as Gaal Dornick is the closest thing to a protagonist, and many of the supporting cast, including Laura Brin, Ella-Rae Smith, Isabella Laughland and Kulvinder Ghir, have played their roles to perfection. Game of Thrones’ Pilou Asbæk as The Mule embodies chaos, anger and psychosis all rolled into one.

Lee Pace – playing cloned variants of the same antagonist across different centuries – is sometimes magnificent as Brother Day, the principal tyrant and galactic dictator. At times he’s hammy, at others he’s boo-hiss villainy, revelling in needless cruelty and caring little for the individual when there’s a galaxy-wide dominion to maintain. Yet, his 170-mile barefoot pilgrimage in season two deepens his character, making him both more and less human. He is excellent in the third season as a stoner version of the same character, becoming sympathetic as he seeks out the courtesan he loved after she has her memory wiped.

Episodes continue to suffer leaps in narrative logic and are still marred by pointless voiceover. Storytelling has declined massively over the last decade or so and those faults are present here. The adaptation continues taking liberties with the original story, largely in the name of maintaining a consistent cast across a generational story. Many will take exception to the race and gender-swapping of key characters. And yes, protagonist Gaal Dornick embodies the biggest of modern storytelling clichés – the girl who is the key to everything.

The incompetent bureaucrats and petty tyrants are predictably all heterosexual white males. Everyone else is inexplicably diverse and gay – including, cliché of clichés, the sailors. Even the nun is called “Brother.” And the empire is secretly run by an enslaved female android. Androids, we come to learn, are matriarchal. The Mule twist at the end of season three, with its blink-and-you’ll-miss-it climax and plot reveal, ruins much that preceded it. The viewer’s ability to enjoy the show will depend on whether these contrivances can be overlooked.

Whatever one makes of these revisions, they unfold against visuals of such scale and precision that ideology seems almost beside the point. The aesthetics are beautiful – whichever version of Unreal Engine is being used, the visuals of endless inhabited satellites and worlds are breathtaking. The colour palettes, art direction and cinematography push the envelope of cinematic grammar. Little in either TV, streaming or cinema comes close to matching the look. Key sets and props owe debts to Hellraiser and Stanley Kubrick.

Perfect? No. Faithful to the books? Again, no. Suffers needless race and gender swapping? Yes. Stunning to look at and credibly executed? Without fail. Does it put everything else currently being produced in the genre to shame? Yes. Asimov’s books are the granddaddy of epic sci-fi and it’s nice to see an adaptation – however impressionistic – attempted. The showrunners should be congratulated for working out how to put the galaxy-spanning story on screen. The scale and scope of their vision make Villeneuve’s Dune movies look like a provincial footnote. Apple, can we have A Princess of Mars next, please?

If you can look past the narrative flaws and accept the show as an interpretation rather than a faithful adaptation, then this is cutting-edge modern filmmaking. Anyone who has tried to read the books must struggle with its ever-changing cast and Asimov’s dated prose style. The series avoids these issues, giving us likeable and hateable characters set against epic backdrops and futuristic vistas. Apple again proves itself the home of premium modern entertainment and streaming excellence. For all the noise and confusion of season three’s finale, season four can’t come soon enough.

Predator: Badlands is Emasculated Masculinity: The Movie, complete with championing disability, taking down the patriarchy – and a cute Disney animal.

At one point in the movie, a creature spits acid at an android and completely melts it away. You know you’re watching a bad movie when you’re envious. Yes, Predator: Badlands is so bad – and will leave you with emotional trauma so acute – you’ll want to find a safe space. Hopefully one showing movies of merit – even torture porn would be an improvement.

Predator: Badlands is a thoroughly enjoyable bad movie – until you stop and think about it. And then it’s just bad. Predator (1987) was 80s machismo. Riotous fun. Endlessly rewatchable and made great by the absurdity of the premise – a group of ‘roided up Reaganite supermen get sent into the jungle to rescue the first rescue team and on the way back get attacked by a trophy hunting alien. It was endlessly quotable, cheesy fun that wore a 40-year groove in pop-culture. Flash forward to today and such grooves are sinkholes filled with the sewage leaking out of modern Disney.

Predator: Badlands is their latest corrupted discharge. The story concerns the misunderstood estrogenic runt of a Predator litter who narrowly avoids being killed by his clan’s emotionally stunted patriarch for bringing weakness and sympathy to the family. Yes, even Predators have daddy issues. Perhaps it’s an Abraham metaphor.

The clichés come thick and fast from then on. Cast adrift in a hostile environment and emotionally vulnerable, our underdog Predator must learn to fend for himself. He does this by deciding to take down the most feared beast on Planet Death – with an extendable glowing sword. Such Freudian subtlety. Unsurprisingly, the weapon he uses against the family at the end of the movie is truly impressive in both length and girth.

Of course, much of the plot is repurposed from the Alien franchise – this and last year’s Alien: Romulus exist in a shared universe. Yes, that pesky Weyland-Yutani corporation is collecting dangerous creatures for – surprise – the bioweapons division. Again. Wasn’t that the plot for the Alien: Earth streaming show too?

The twist – unsubtly signposted halfway through – kills it. The ending steals the power-loader from Cameron’s Aliens. The story even manages to revisit the wolf pack cliché from The Hangover movies. In the end, Predator finds his emotional support animal and his new tribe – the friends he makes along the way. Vomit.

The singular best line in the movie – the last one – made many in the audience laugh out loud. Yes, it threatens female Predators in Part 2 – of course it does. So, we have domineering females to look forward to that’ll no doubt make the preceding movies look like a hen-pecked boys’ golfing weekend.

When it’s over, you’ll want to applaud the awfulness of what you’ve just seen. The biggest weakness is letting the Predator speak. The filmmakers have turned the character from the Ed Gein of sci-fi into something with human motivations – current year safe space culture motivations – and it is thoroughly boring. Its language seems only to express patriarchal platitudes. It’s not alien if it has your emotional drives, now, is it?

The film does have some technical merit – as the saying goes, it’s at least in focus. The environment and the hostile creatures are functionally done – a bit like a holiday in Australia. However, the Predator design is terrible – the crab-like original is iconic and, of course, someone thought they could improve on it with cheap CGI. Could they not just have used Sora? The Predator home world is dull – they seem to live in a desert that’s less convincingly alien than Vasquez Rocks – which goes no way to explaining what shaped their hunting culture. So, everyone’s hometown sucks? The Predator body suit looks like a cheap Halloween costume.

The two redeeming parts of the film are Elle Fanning playing the goofy over-optimistic android Thia and the more callous Tessa. Thia has literally been torn in two. Her legs still managed to kick-ass though. She gets all emotional at the thought of her duplicate being her sister. Predator takes her along on his hunt for company, referring to her as a tool – scissors, presumably.

So, Predator becomes another classic property reduced to 2025-standard slop. We keep hearing this is the worst decade for movies since they began and on the strength of this film, that is hard to refute. The original film was a textbook example of pacing, creativity and tension. This film has had the adrenaline gland removed, replacing fun and clever with coincidence and feelings. Perhaps studios could stop trying to make everything “relatable” and rediscover spectacle instead. For the art of filmmaking — and for whatever’s left of the audience’s dignity — Predator: Snowflake’s First Hunt really shouldn’t exist. Seeing this on the big screen feels like going back to your abuser for another predictable beating.